Wednesday, May 12, 2010

Saturday, March 27, 2010

SACRILEGE, group show,18 march 2010

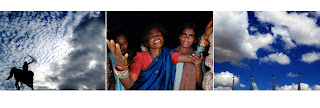

AJILAL, reminiscence ( triptych )

AJILAL, reminiscence ( triptych )

photograph on archival paper | 50 X 71 cm X 3

AJILAL land of it’s own sky ( triptych )

AJILAL land of it’s own sky ( triptych )

photograph on archival paper | 50 X 71 cm X 3

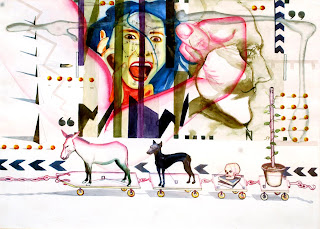

DEEPAK WANKHADE, untitled

mixed media on paper | 26 X 32 cm

DEEPAK WANKHADE, untitled

mixed media on paper | 26 X 32 cm

JEEVAN.R, birdscape studies

JEEVAN.R, birdscape studies

mixed media on paper | 87 X 144 cm

JEEVAN.R, birdscape studies

mixed media on paper | 87 X 144 cm

NISHAD.M.P, false hypothesis

NISHAD.M.P, false hypothesis

dry pastel on paper | 180 X 120 cm

NISHAD.M.P, untitled

NISHAD.M.P, untitled

dry pastel on paper | 86 X 66 cm

NISHAD.M.P, untitled

NISHAD.M.P, untitled

dry pastel on paper | 86 X 66 cm

RAJESH.P.S, occupied space, given by you

RAJESH.P.S, occupied space, given by you

dry pastel on paper | 75 X 55 cm

RAJESH.P.S, untitled

RAJESH.P.S, untitled

dry pastel on paper | 75 X 55 cm

We can feel some kind of positive transformation happening roughly within our collective existence. Even if there were lot of probability in abundance existing to

sabotage it, as happened repeatedly in past, but such a hint itself is revitalizing.

This stimulation is very evident in art panorama and dalit focus. In the art vista

instead of depending absolutely upon art galleries, formation of many groups take place and in dalit issue, so many great studies and struggles take place. That is why we are incessantly partaking in such movements via our shows.

Assigning a show like sacrilege can by far be observed as a bit obstinate

linked with the anti theological/atheistic agenda. However it has no correlation

with such dogmas. But by means of that name ‘sacrilege’ what we propose is the

articulation of our notions allied with the art and politics. Each participant in this

show has their own unambiguous political thoughts which they endeavor to execute in their works. And above all, they all were trying to converse about the bigotry existing in the present societal subsistence. That society occupies the whole lot, in particular the art space and dalit space. Each time when we plan a show, we happen to be blamed on the corner of selection. What the demand is that it should be based on the so-called notions ‘pure’ and ‘good’. It is habitual that each one persuades to determine and ultimately declare the quality of art and divide it into two categories as ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Where from this tendency comes out? And other notion is about the ‘purity’ and ‘impurity’ of art work.

Why the impure and pure? So these two ideas put forward an authority that has the supremacy to put judgments. Consequently such fabricated authoritative statements assert an alien body, which is burried but active in our thought process. As these terminologies are always connected with the conventional social analysis we should be keen about such usage.

This political alertness is very obvious in our intentions and observations. Ajilal’s

comment: “I am talking about my intentions. Not about the result of my art. On this show I took a divergence from my earlier art practices. I believe my works shouldbe more direct. Then there arise the chance of losing its aesthetic ‘something’. But Ibelieve that is a ‘must’ in our time………..” Rajesh observes: “What I try to articulate is the disparity between the huge male concrete formations and wiped out female existence…..the problem of the genuine and usual space occupied by reprehensible.” Nishad: “[……. for the growth of a plant there is no need of natural conditions.] As the religion tries to manipulate the body, capital formation also demands a comatose artificial society. It is a kind of plucking away or adding upon the inappropriate or creating upon inapt space/condition” .Deepak: “…..inner turmoil, sufferings that represents society…..” Jeevan: “presenting cart puller as a mover of history, piloting

history and attempting to carry the whole load above him and place it elsewhere in a safer abode, has a metaphor of moving “dwellings” related to mass migration with the idea of moving landscapes.” Hence our ‘society of works’. Each of this work cannot be considered as self determining one devoid of external relations. It exists simply in relation with others. A work of art is not an entity with an auto telling mechanism. But it should be envisaged as an evocative contemplation unambiguously related with so many other thoughts outside the currently discernible frame.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

SACRILEGE, group show,18 march 2010

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

PROFANATIONS, art show, feb 22 to 28, durbar hall art centre, kochi

VINU.V.V UNTITLED,WATER COLOR ON PAPER,150CMX90CM

VINU.V.V UNTITLED,WATER COLOR ON PAPER,150CMX90CM

VENU.R, AROUND THE THRONE, WATER COLOR ON PAPER,70CMX115CM

VENU.R, AROUND THE THRONE, WATER COLOR ON PAPER,70CMX115CM

SIVADASAN,FEAR IMAGES-3, OIL ON CANVAS,92CMX115CM

SIVADASAN,FEAR IMAGES-3, OIL ON CANVAS,92CMX115CM

HOCHIMIN, THE SOLITARY MONOLOGUE, OIL ON CANVAS, 180CMX120CM

HOCHIMIN, THE SOLITARY MONOLOGUE, OIL ON CANVAS, 180CMX120CM

Retaining local identity- a visual way

SUDHEERAN.R

To construe or to describe a work of art is an unattainable task to me like any ‘layman’. But I suppose everyone has their own right to simply talk about an artwork. Moreover no one can ever produce a final meaning of any cultural products and each artifact is subjected to multiple interpretations from different subjective locations and positions. Here I locate myself doubly as a friend as well as the so-called layman and thereby deploy friendship as a trope to enter the interpretative paradoxes of works of art. Further, through this positioning I attempt to assert a ‘layman’s’ right to read and interpret a work of art which is conventionally a domain of the cultural elites.

Anil presents himself as a cheerful man with sparkling plump cheeks along with an array of penetrating laughs waiting to be unfolded. While he always keeps his local mannerisms alive, he presents himself everywhere as the way he is. As friends knew, he is very fond of food and in particular his passion for fish is an open secret. He can’t fine-tune himself to a ‘pure’ non-fish atmosphere and within no time he finds himself a misfit to that space or occasion. His life in

His decision to retain a local identity and a careful overview of the character of images accumulated by him indicates the presence of a micro-politics in his works. This micro-politics seeks our urgent critical attention especially in the socio-political atmosphere of Kerala where everyone is made-up as ‘internationals’. On one occasion K.P. Reji observed that, “When I look at a water tank through the windows of my studio, I do not think about the international water politics. I see the water tank as an image that encodes the locality. It simultaneously registers my existence within and in relationship with the local.” Anil tries to praxis this localism in his own way. Actually, to him it is not a kind of practice in the conventional sense, but an act of partaking in a process of being and becoming local. Knowingly or unknowingly he collects everything as his own local image.

During the 1970s there was a Malayalam poem named ‘Kattutheeyil Petta Kudumbam’ (A Family Caught-up in the Wildfire) as part of the study material for primary standards students. But it transcended the status of study material and trespassed into so many hearts. Among them, few keep it still as a haunting and painful memory. I think Anil is one among them. From this painful and haunting memory he collects his major images, ‘fire’ and ‘bird’. Envisaging locale around and at once, he always reserves an open eye towards his own mind pool. Local happenings and many haunting memoirs mingle together in an atypical way within his works. How he identifies the holy cross as his own image in one of his earlier works also acquires significance in this context. He visualizes it as a Kuzhikalian cross with asymmetrical shapes at the same time facilitating shelter to birds in its tree-like branches. This poetic metaphor of the simultaneity of death and life, shelter and abandonment is a constant thematic of Anil’s works. In other words juxtaposition here functions as a semantic binding of his works.

The usage of poetic metaphors needs an elaboration in this context. For instance, all of the three sets of works in this present exhibition can unravel their complexity only through a subtext which holds them together. One can argue that these works have a hidden narrative which speaks of the travel of a subject from a living tree to a wood log. Here Anil attempts to depict the different facets of life. Hopes, disasters, death, interruption all are present here but interestingly the metaphor of death which is represented through the wooden log also clearly suggests that death appears here not in the sense of an end but as haunting presence of memories. In that sense, they are not mere poetic metaphors in the conventional sense but are attempts to hold together subjective ambivalences of a subaltern self. On canvas he attempts to create a manner of blend, linking devastated dreams from different genesis and memories from his own mind reservoir. The hole in the tree trunk, the diamond necklace, the hammered nails and the demon-like little opened mouth of the trunk altogether creates an atmosphere of pathos. The necklace in the work can go beyond the anticipated score of an average story. Necklace is rare and precious, but nails are common and worthless. Both were positioned in a single space – the dead tree. Through this act Anil attempts to articulate a new perspective of fate. Here he negates the solace of tranquility offered [allowed] by the tightly fenced mainstream region; as each and every nail takes you back to the commune of possessed (in past, present and may be in the future margins of history). Nails are the time-honored means to eliminate or erase the insanity or alternative/unfamiliar notions – it is deployed by the hegemonic forces as one of the major tools to guard the sanctity and safety of the mainstream at each time.

Dreams are never solutions. But they can sometime emerge as the legitimate or illegitimate account of our wishes. His dreams comprise ruins and hope. In the work The Miraculous Rain Clouds, he accomplishes the permeation of a divine rain. The goats never gain entry to the region of that rain. But they gain an opening to a new way of life by peeling out their “scapegoat coat”. Is it a true transformation? The hills erecting as the manifestation of mundane stupidity plays the counter act. His triangle shaped hills always appear resembling roofs which can be conceived as refuges. But by its obscurity and mendacity, it itself negates that sense. It is a journey towards the big process of becoming erasures.

However, it is imperative to mention here that, in the context of Anil’s pictorial strategies one can propose fewer observations which are central to the receptive process of work of arts in general. No work of art is a singular entity. Each one is manifestly related with the meticulous other. Tracing the interrelation amid works based on the visual receptivity is what produce fruitful dialogic world. This alone will aid us to hear how and what the works echoes. Ones connotation acquires critical resonance only with the mention of other. It is a kind of reading ‘in with the others’. This understanding negates the sovereign existence of a work of art. Or rather, it tries to establish the existence of a ‘society of works’.

REHEARSING THE DRAMA OF HORNS: HOCHIMIN’S RECENT WORKS

BENOY.P.J

One of the aspects central to many strands of populism is the constant evocation of a generalized consensus to the detriment of all dissenting/ different voices. The nation, in such an imaginary, figures as a plurality that seeks recourse to homogeneity so as to function more efficiently. Hochimin’s work refuses to take to heart such a short-circuiting of culture and instead attempts to create ‘Solitary Monologues’ which are necessarily musings from the midst of life that foreground the possibility of putting out new sprouts into an arid zone. Though the structure of the emerging globular protrusion from the ground reminds one of the works of Jyoti Basu, here it starts to signify differently. In the paintings ‘The solitary monologue’ and ‘The ins and outs’ while this protuberance appear in all singularity and calls forth a concentrated attention, in ‘The Attendant’ the plurality of their presence adds to the narrative an added dimension. The

REHEARSING THE DRAMA OF HORNS

What happens when a man is all horn, so much so that the head disappears altogether and is replaced by horns in its place? Is it the mere disappearance of the head- or is there something that goes beyond it? Maybe a head that makes itself into a horn. Who then, will sound this horn? Is the head irretrievably lost? Or is there a music in which all that is lost is regained? To Hochimin the drama of horns is something that he has been rehearsing for a long time now. Is it the strange way in which the common man’s body (marked red) is transmuted by the workings of power that is alluded to in these works?. While it is common enough for paternalistic movements to have intellectual leadership coming from the elite strata, the common man recurrently figures as a mindless and senseless brute who need to be coached in the civilized language of the elite to act in a meaningful manner at all. Intellectuals coming from minor communities are derided as stooges of the State/ imperialism or the ruling class, or of patriarchy, while the elaborate ties/arrangements maintained by the caste-hindu elite leaderships with regard to Power are seldom submitted to close scrutiny. It is perhaps this ambivalence that a painting like ‘The Attendant’ attempts to address. The reduction of subordinated people into mere objects, bodies and so on, without any active part in the reconstruction of their own fates is a common enough racist fantasy, Hochimin, in a simultaneous move exposes/ problematizes this working of the ‘majoritarian’ imaginary and point towards other modes of minor becomings which destabilizes or undermines Power.

In ‘The ins and outs’ again plays with the globular presence, this time closer and more immediate, but the almost classical figure in the foreground with its headphone is almost unaware of the goings on, immersed in its own favorite music on the one hand and in a red cavity (catacomb ?) on the other. The top portion here is an ambiguous space which could well be the ocean or the sky or maybe an indefinite continuum of these.

In his earlier drawings like ‘The horseman’ and ‘My name is….’ (alluding perhaps to the controversial hindi film.) Hochimin’s work constantly examines political strategies that fail to touch core problems (glove and the microphone; caste hegemony and the reduction of the subaltern to a headless beast) even while aspiring towards populist goals. However the addresses to the popular are not singularly negativistic here, since the work sets out to dwelve within the popular in such a way that the strategies of power inherent in the working of hegemony are exposed so that other perspectives could start playing significant roles.

A Polyphonic Allegory: Recent Works of K.C. Sivadasan

SUNIL.G

While engaging with the work of K.C. Sivadasan, it seems as though the artist goes through his typical habit of encountering life realities that in fact propels him to the act of art making itself. He remarks “even the very state of mind at the time of painting influences the work of art.” His painterly language and the subject matter underline this statement. It is because of this unadulterated approach towards art and life that he sustains himself as a working artist and at the mean time a layman. This contradicting facet of daily life never engenders a pseudo character to his approach; instead it generates varied tropes through which the artist addresses his own individual self and the social self which are central to the practice of art. Following this trajectory one could easily recognize the distinctive layers of narrative in Sivadasan’s works; they are linguistically surreal and expressionist in character.

For Sivadasan, the act of art-making is a sort of self-tackling; bringing about the experiences into an open space of dialogue to encounter the social dimensions involved in it. And in the meanwhile he also adopts techniques which enable him to self-evaluate the receptivity of his own art work. As a layman belonging to the economically weaker section of society and a man haunted by the memories of subaltern childhood, Sivadasan’s fascination towards the aspect of surreal was quite spontaneous. Actually there occurs a dissection of the real experiences when he executes them in canvass; at the meantime he relishes the spontaneity of art creation as it frequently grows beyond his initial conceptions and structures a different array of visual dynamics.

Evidently Sivadasan’s works depict different layers of spaces unyielding to the normative representative strategies which are structured around the distribution of spaces in an ordered manner. He also adopts a polyphonic narrative instead of a protagonist centric narrative giving focus on its multi vocal verbality. Because of the presence of this polyphony, in his painting, any in-significant object can raise questions which are conventionally beyond the ambit of their tongue. He doesn’t fix a nucleus for the narrative, instead images-subjects stream in spontaneously breaking any sort of monotonous converse. Perhaps he illustrates several micro-narratives within the text possibly enough to create cavities in traditional interpretations; often such openings disrupt the pre-fixed contexts of a surrealistic narration.

Images he opts may be from his life surroundings or from his visual/literary experiences but in the course of their depiction, they undergo a process of transformation indicating definite signs of the time and space around him. The chosen elements for depiction turn significant as they semantically interact with the context they are placed in and engage in various interplays to derive openings for further dialogue. For instance, several unappealing particles like the metallic ornaments of a classical wooden door in Throny images- 5 leads towards subtle but politically pointed contexts. That particular image within the narration alludes to the expired state of feudalism, for which such ornamented wooden doors were symbols of might; Sivadasan thereby brings in a valid note for thought as he reinitiates the residues of expired feudal might into the discourse. Similarly he recites copious historical- cultural references through related imageries.

The way he orders these images opens another intricate exchange that of narrowing and negating. At times the indistinctiveness between images and its shadows offers metaphorical existence to the shadows. Thus often shadows of images do attain material vitality within the narrative as they get absolved from the image; thereby re/de constructing the narrative existence of the parent image itself. Obviously that leads to a sort of interplay bartering the notion of real between the image and its shadow. Interestingly Sivadasan does an interpretation of the above said interplay in one of his works titled Thorny Images through the representation of a whirling top, which when released attains freedom from its thread which had already set the destiny for the top but still it manifests new dimensions by making use of the state of freedom while whirling.

We could trace the thematic of ‘abandonment’ as being frequently rendered through objects, imageries and desolated terrains in his works. Emptied mud pots, rusty metallic wheels, hooks, a released top, shed feather, dead bird, broken egg, abandoned bag, ruined structures, lonely bushes and creatures; the recurring presence of these imageries constructs the atmosphere of an abandoned beingness. Expressively initiating a discourse on the power-knowledge relationship of images (frequently he traces parted materials that belongs to perceptible power hubs) the question of ‘abandoned’ gets reinitiated and the multi-layered means of power exertions get manifested.

An image of a bird caged in its own skeleton seems repeatedly depicted in his works. Although it articulates an easily interpretable exchange of victimization, this image remains particularly nuanced with the complexities of existence haunted by the abundance of abandoned terrains. His latest work Fear images-3 deals with a similar image delivering the pictorial irk of a desolated locale, which straightforwardly evokes the memory of the shore of backwaters. The habit of coalescing images to form rather complex imageries indicates the influence of poetic imageries and metaphors in his works. Naturally it can be linked with the sensibility of Malayalam modern poetry that has had an in-depth influence on him.

His preferences for dark coloured backdrops and his evidently traceable practice of bright colours convey a specific character desperately intended to deliver the tenor of a haunted reality. His painterly habits and practices share elements of popular visual vocabulary, which he frequently practices as a ‘professional painter’ for his daily earnings. While working in the realm of ‘high’ Art, he deliberately pursues similar colour patterns which are intimately closer to his experiences. Along with the imageries, his colour pattern also proffers a peculiar defensive content to the works, which the artist regards as an individual practice of survival. In short, these works can be read as poetic metaphors of human existence in general and at the same time as allegories of subaltern existence in particular.

Deconstruction of the Architecture of Thought

SUDHEERAN.R

Each and every work of art endeavors to practice a type of negation and assertion of descriptions recurrently. Whenever we attribute a quality/meaning to something there arise the chances of evading other meanings/qualities. Further, approbation includes the process of criticism as well. Facing a similar predicament with the ‘meaning’ at various crossroads, one should get hooked into the anecdotal societal circumstances and its relentless manifestations. As meaning and image are interwoven in most instances, the artist is often confronted with the dilemma of the work generating multiple, and often contradictory connotations. Or in other words, meaning of an object is not always stable. In our time, subsuming an object within an image is not a trouble-free assignment. On every occasion, the artist needs a space to displace it. Therefore the process of making a choice of the image will turn into an ardent pain for the artist. Subsequently, it needs an insightful social receptiveness additionally in order to surmount the dilemma.

Actually, it is not the crisis of the artist alone. This problematical aspect involves three visages. On the one hand, it assails the artist and on the other, it attacks the writer who tries to make some meaning about the work of art; and finally it attacks the work of art itself. So the notion of ‘eternal work of art’ disappears and so to say the writing also becomes an impossible possibility. As a practicing artist, I think R. Venu is extremely/aware about this discourse and in order to engage with this complexity, his works locate themselves not in the realm of the ‘individual’ but in the realm and realities of the social. The social appears here as the gravitational source which solidifies his representational strategies. For instance, selecting an animal as an image is not an unproblematic act in our time where the trope of animalization is largely in circulation to deride the marginalized. Taking this possibility’s danger as responsiveness, Venu transcends that sphere with his always receptive political organs. Through the portrayal of donkeys, Venu attempts not only to indicate their masters but also to sketch their life outside the safe boundaries of the mono-structured world too. It is evident in the fact that the class/caste of the master is indicated through the ‘high class’ of his pets as it is customary that all castes don’t have the autonomy to keep all the animals as their pets.

Donkeys often look downwards, but in few instances they look skywards inattentively. According to the Brahminical edifices, concentration and veneration is considered as the most pulsating excellence and it is recommended as a means of upliftment. For instance, in these edifices, the metaphor of horse is the hypothetical antonym and they intangibly correlate all accomplishments with their power to be attentive. So the downtrodden never get entry into the enormous and cleanly built regions belonging to the ‘uplifted’ class. But at the same time, the so-called uplifted class needs the subjugated to exist in the form of mere metaphors. Or in other words, in the dominant imagination, the marginalized exist only as mere signs. Against this imagery, through locating the donkey in the middle of a feudalist labyrinthine architectonic setting, Venu proposes the fallacies of the dominant imagination. The political acumen of Venu recognizes the emergence of various subaltern discourses and responds to it productively through this representation. Even though the inverse logic has its own problematic, gesturally, his move marks a positive political act.

The usage of blue to indicate the open space deserves more critical scrutiny here. The colour blue appears here as the metaphor of an imagined ideal world. This world is systematically distanced from the trivialities of the everyday world. The construction of an imagined ideal world is central to the sustenance of dominant discourses. For instance, the construction of tribal/village life as organic, pure and close to nature allows these dominant discourses to distance our attention from the actual life conditions of these communities. Many of the representations of tribal communities in the mainstream movies are a case in point. Against these propagandas of dominant discourses, Venu demands a proximity which denudes the illusive blue. The sea or sky remains blue only within a prescribed distance. It is a mirage. Further, the representation of flying crow and crane amplifies the presence of a proverbial world where subaltern emancipations are ridiculed in the everyday life world. Through this usage of blue as the outside world of the labyrinthine inside, Venu indicates not the ‘other imagined world’ but the close connection between the inner and outer world. In short, his works speak about the modalities of Brahminical cultural imperialism.

Similarly the centrality of the throne in another painting also deserves a close scrutiny. The posture of that throne is depicted as the antipode of donkeys. It looks upwards vigorously in a disposition of conquering. This mood is executed well by the visual balance of buildings, steps and tunnel patterns. In first cognition we can feel this pattern as the output of repetitions, but we will soon recognize that the application of repetition is more than just a style that fulfills nothing beyond the furnishing of those huge buildings. But the constructions and the colors specified to the edifice helps the work to generate a temper of menace; but more significantly of imperceptible presence of the almighty, omnipresent state and its close proximity with dominant cultural values. Along with the skyscape and the presence of the flying crane and crow, the binary logic of the dominant discourses and their hierarchically ordered worldview is thrown open for an ardent criticism.

Surpassing the Subscripted Beingness

G SUNIL

V.V. Vinu’s works in this particular show inscribes a definite deviation in his artistic trajectory bringing in human images to subject positions and thereby problematzing his own self within the text. While marginal imageries were the predominant subject matter of his earlier works, having indistinct structure-identity exemplifying the pictorial urge to transmute, Vinu’s recent works significantly put forth a different context and position the artist himself in a subject sphere afar from realistic perceptions. When read so, one thing obvious is his intentional interferences in language so as to implant complexity that may denote the intricate contexts evolved in the subject he deals with.

Plausibly when the artist himself becomes the protagonist of representation it does converse a biographical thematic; Vinu’s recent works adhere this logic while putting across firm discontent to its usual rhetoric. Apparent traits of the real life (artist carrying black and white carry bags, he in a posture as if posing for a photograph) in his woks are subjected to a narration upholding an interrogative skepticism over its perceptual identity. The way he textualizes the protagonist demands a distinct and careful reading altogether. The shortness and stoutness of the physique that he depicts along with the fatty nature, the belly and complexion of his individual physical character are worthily espoused here. Certainly such a physique stands contrary to dominant visual representational strategies of the celebrated male physique in popular cinema, advertisements and other narratives. Vinu’s self representation here is extremely nuanced; disconcerting the normative representation of an ideal male figure. This aspect becomes worthwhile particularly in the context of the cinematic representation within Malayalam film industry where the Calibanic misrepresentation of minor identities as dark, short and users of colloquial vocabulary are rampant. For instance, the self-representation of a celebrated Malayalam film star, Sreenivasan and the absorbed notion of inferiority inscribed in his characters can be juxtaposed with Vinu’s subversive strategies of representation. Representations such as the inferiority complex-ridden characters of Sreenivasan always contribute to the sustenance of the ‘ideal’ physique of an ‘upper-caste’ male. A critical reading on the representation of physical characteristics in the context of its social structure allows us to engage with various political symptoms. Notions embodied within the social psyche stumble on such individual features in order to mark the caste-racial identity of an individual (even a beard serves for racial marking and victimization).

The artist in his particularly favorite garb – a blue stone wash and black jeans – appears to have adopted a dress code to become subject of/to observant scrutiny. In a political situation where particular dress codes have emerged as elemental for the state to mark as involving anti-state terror activities, (activists of a dalit group, DHRM, in Varkala, Kerala were branded as terrorist on the basis of their unique dress code – black T-shirt and blue jeans) Vinu’s eagerness to dress himself in a similar code does exceed his personal or habitual likes and dislikes. Perhaps his physical representation in these works spreads an annoying vibe towards predetermined reading exerting an unambiguous statement of problematic beingness within the ‘sacred realm’ of cultural practice.

The work ‘Return from Market’ proposes another context of complexity where the protagonist himself handles the contradiction of ‘purity’ and ‘impurity’. The white carry-bag in the representation signifies the notion of vegetarian/purity while the black carry-bag on the other hand signifies the presence of non-vegetarian/impurity aspect. The protagonist seems to carry a white one in his right hand and a black one in the left hand; perceivably they contain vegetables and flesh respectively. This moderately suggestive representation of black and white binary problematizes the cultural codes that construct the worldview of hiding the flesh and exposing vegetables. Deep rooted mental shamefulness in exposing an individual’s non-vegetarian identity does decipher its customary origin to a structured social psyche that performs the discerning act between the pure\vegetarianism and impure\non-vegetarianism. In another instance an over-turned sacred lamp and a lamp with long anchor tail appears to be held by him; here the held objects\motifs infer the questions of purity/sacredness – purity in the sense of social sanctity appropriated through immaculate cultural propagation. Thus the imbibed notions of pure/impure in such objects are unwrapped in a common space so as to engage them in the discourses marked by socio-cultural codes.

An observant reading of his works identifies several suggestive nooks eliciting the perseverance to practice popular language. While characterizing faces, Vinu adopts the popular painting style of cut out portraits (portraits of film stars copiously discernible in south

Assenting to S. Santhosh’s observation regarding Vinu’s work, (his water colours are the painterly depictions of his sculptural desire[1]) we could easily observe a conspicuous break away from it as his recent works attempt to attain a rather painterly language. In his earlier works, an atypical usage of black in depicting images so as to signify the oddness of a minor existence remains evidently traceable. But unlike his previous works the central images (self portraits) here relish prominence while the yellow backdrop turns whitish. Doesn’t it envisage the pro-activation of a social self sharing the common experience of subjection to being minor? Ambivalent emotions expressed by the protagonist holding a sacred lamp invites heed as it conceivably suggests a problematic. The measure of insolence towards the sacredness of the object\motif, and also his gestures – the firm grip and the distinguishable posture – bid an attitude of activism. Self imposed blindness in another instance, duly incites active discourses within the proposed act of self- motivation.

Perceivable initiation of a reasonably ‘subscripted beingness’ seeking open spaces for dialogue can be decoded from Vinu’s works. His recent works transmit an unquenchable craving for further democratic spaces to surrogate the practiced cultural environ of purity/sacredness.

[1] I refer here to the note by